January 16, 2026

Disability and Work Topics 101: What Is Stigma?

Disability and Work Topics 101: What Is Stigma?

Authors: Lauren Renaud, Melissa Pagliaro, Rachel Bath, and Michelle Willson

Visuals By: Melissa Pagliaro

Audio Narrator: Noor Al-Azary

Introduction

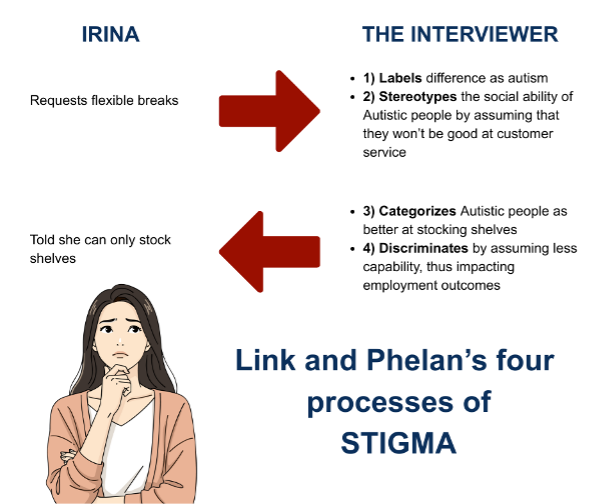

Meet Irina. She has strong customer service skills and is looking for full-time work. She applied for a customer service job at a local grocery store and was invited for an in-person interview.

Irina is Autistic1. During the interview, she asked for flexible breaks as a workplace accommodation. This would allow her to step into the break room if she needed time away from customers or was experiencing sensory overload.

The interviewer was interested in hiring Irina but doubted her ability to succeed in a customer service role because she had the mistaken idea that Autistic persons have poor social skills. When the job offer came, it was not for the customer service role that Irina applied to and was qualified for. Instead, she was offered a shelf-stocking role. The interviewer thought Irina would do better in a role that did not require person-to-person interaction.

Irina’s experience is an example of stigma. The interviewer made assumptions about her abilities based on the accommodations she asked for. As a result, she was denied the chance to work in a role that matched her skills.

In this blog post, we will explore what stigma is and how it can impact employment for persons with disabilities.

What is Stigma?

Stigma is what happens when certain people or groups get unfairly judged, labelled, or treated as “less than.” It’s not about something being wrong with a person but about how society responds to differences.

The idea of stigma has been around for a long time. Back in the 1960s, sociologist Erving Goffman described stigma as a “spoiled identity”, meaning that one negative label, such as having a mental health diagnosis, can overshadow everything else about a person2. His work shaped how people talked about stigma for decades.

But researchers later pointed out some gaps. Goffman focused on the person who was labelled and not enough on the people and systems doing the labelling3, 4, 5. He didn’t fully address how stigma connects to power, discrimination, and exclusion.

Today, stigma is understood as something much bigger than a label. It’s a social process that happens when people with more power decide that a certain difference is “bad”, attach stereotypes to it, and then use those ideas to justify unfair treatment.

For example, ableism is a form of stigma that devalues persons with disabilities, often by assuming that “normal” means not having a disability. This shows up in everyday attitudes, inaccessible spaces, and policies that exclude people.

Seeing stigma this way helps us understand not only where it comes from, but also why it leads to real world-harm. This more modern view sets the stage for frameworks about stigma like Link and Phelan’s, which explain how labelling, stereotyping, and discrimination work together to affect people’s lives.

Link and Phelan’s Four Steps of Stigma

According to Link & Phelan (2001), stigma exists when:

- People recognize and label differences in people.

- Societal beliefs link differences with negative stereotypes.

- Labelled people are separated into groups like “us” and “them.”

- Labelled people are rejected and discriminated against – damaging their social standing, reputation, opportunities, and outcomes3.

Let’s look at these four processes through Irina’s experience.

Stigma and Power

You may wonder why certain traits are linked to negative stereotypes while others are not. For example, Irina’s hair colour was not associated with a negative stereotype, while her accommodation needs were. As Link and Phelan describe, this is because of systems of power.

Our society is built on hierarchies. For example, White men are more likely to be in positions of power compared to women or people of colour3. Those in positions of power often create or reinforce expectations about how people should look, behave, etc.3 For example, in Western cultures, the neurotypical majority often sets and reinforces expectations that people should make small talk and eye contact. These behaviours may be valued and rewarded in the workplace, offering employment and advancement opportunities for those who make small talk and eye contact.

In the next section, we will talk about the impacts of stigma, including discrimination. It’s important to remember that while discrimination can look like a person doing something bad to another (for example, not hiring a person with a disability because of their accessibility needs), it can also be structural (for example, inaccessible workplaces, lack of funding for accommodation supports)3. Both kinds of discrimination are based on power structures in our society that disadvantage people who are negatively stereotyped.

The Impacts of Stigma

Stigma can involve acts of discrimination, including intersectional discrimination, and the person who experiences it may find that their self-image is affected. In turn, their willingness to disclose their disability in the workplace may be negatively impacted.

Discrimination

People who experience stigma, or people who are stigmatized and stereotyped, can experience discrimination in many ways. Discrimination may happen person-to-person, like between employers and jobseekers with disabilities. For example, employers might6:

- Be reluctant to hire persons with disabilities.

- Deny accommodations.

- Pay persons with disabilities less than their colleagues without disabilities.

- Give workers with disabilities certain tasks or responsibilities that are seen as “easier.”

- Give workers with disabilities fewer opportunities for learning new skills and receiving training.

- Not consider persons with disabilities for raises, promotions, or leadership opportunities.

- Encourage workers with disabilities to retire or leave their role.

- Dismiss workers with disabilities without cause.

Discrimination may also occur between workers with disabilities and co-workers without disabilities. Co-workers may6:

- Not want to work with people with disabilities.

- Think workers with disabilities need to work harder to prove they can do the work.

- Be overprotective or over supportive, leading to less opportunity and independence for workers with disabilities.

Discrimination can also be structural, or appear through practices in the workplace, like7:

- Signage that is not accessible (e.g., low contrast, poor lighting, inaccessible font).

- Paths that are not accessible (e.g., passages that are not wide enough for mobility devices).

- Washrooms that are not accessible.

- Lack of compatibility of online documents, websites, etc. with screen readers.

- Lack of captioning.

- Cost of assistive devices and technology.

Self-Image and Disclosure

Stereotypes and discrimination can harm the self-image of persons with disabilities. Persons with disabilities may internalize stereotypes, meaning they start to believe it about themselves. This can lower their self-esteem, discourage them from asking for help, affect their mental health, and reduce their interest in social activities6, 8. Persons with disabilities may hesitate to seek work or promotions because they expect stigma and discrimination6.

Some persons with a disability may choose to hide their disability or accommodation needs to avoid stigma and negative stereotypes9, 10, 11. Although this can be a strategy for avoiding discrimination, it is a lot of work and might not be possible to do for those who need workplace adaptations or those with visible or apparent disabilities.

Intersecting Stereotypes and Discrimination

The impacts of stigma can be intersectional – people can be stereotyped and discriminated against based on differences in gender, sex, sexual orientation, race, ethnicity, Indigeneity, age, body size, income, educational attainment, primary language, religion, geography, and more, in addition to their disability type.

Let’s look at an example of intersectional stereotyping and discrimination. Meet Jabari, a Black man with a mental health-related disability. People with mental health-related disabilities and Black men can both be stereotyped as being unpredictable and violent3, 12.

While at work, some colleagues treat Jabari like he is unpredictable and dangerous based on their beliefs about his race, gender, and disability, even though he is neither of these things. For example, they avoid giving him direct feedback out of fear that he will become angry. They also ignore him in social situations in case they say something that might “set him off.”

Jabari can’t be sure which part of his identity is being stigmatized by others. Instead, he feels it is the combination of these identities.

To learn more about intersectionality, check out our blog post: Disability and Work Topics 101: Explaining Intersectionality and Disability | Canadian Council on Rehabilitation and Work

So, what can we do to challenge stigma in our society? We will explore this next!

Addressing Stigma

Stigma continues to change, with new labels, stereotypes, and ways to discriminate being created as time goes on3. For example, now you might hear myths about autism being caused by vaccines or by using acetaminophen during pregnancy. The changing nature of stigma makes it difficult to address in our society. However, Link & Phelan (2001) emphasize the importance of addressing both person-to-person and structural discrimination. Addressing the behaviour of a group (like employers) alone is not enough to dismantle the wider problem of societal stigma3. Efforts to address stigma must target multiple levels3. Some ways we can address stigma to make sure we’re tackling it in several different ways can include8, 13:

- Normalizing disability as part of the human experience and not something to fear or distance ourselves from.

- Showing that accommodations are for everyone.

- Recognize the role of society and the environment in creating barriers that exclude people from participating.

For more on barriers, check out our blog post: Disability and Work Topics 101: Understanding “Barriers” for People with Disabilities | Canadian Council on Rehabilitation and Work

- Improving representation in media and decision-making.

- Promoting disability awareness and education.

- Challenging disability-related discrimination.

- Listening to the perspectives of persons with disabilities.

- Getting involved with and supporting disability advocacy groups.

- Creating strong and lasting policy environments that enforce inclusion.

Addressing stigma is a collective responsibility. Let’s look at what could be done in Irina’s case.

Employment service providers and advocates could play a large role in addressing the challenges Irina experienced. For example, they could educate the interviewer on the value of accommodations for all workers and teach the interviewer about how the workplace environment is the challenge, not Irina’s disability. The interviewer could be encouraged to hire persons with disabilities into management roles and bring in experts to talk about disability and inclusion with all employees. The interviewer could also be reminded that they have a legal duty to provide reasonable accommodations, and flexible breaks would be a reasonable accommodation.

Those in leadership roles in the workplace can also make a big difference in addressing person-to-person and structural discrimination. CCRW has many resources leaders can use to address stigma in their workplace!

Resources

Want to learn more about how you can create a stigma-free workplace for jobseekers with disabilities? Check out CCRW’s Disability Confidence Toolkit. You can also check out our job board and resource hub, Untapped Talent. In Untapped Talent, you can find our Disability Confidence Training and AccessPath – our new tool for assessing workplace gaps in accessibility.

To learn about hot topics in disability employment, check out our Trends Reports!

Notes and References

- At CCRW, we are committed to using language that reflects the values and preferences of the communities we serve. In this blog post, we adopt identity-first language (e.g., “Autistic individuals”) to align with how many individuals in the Autistic community self-identify. We also capitalize Autistic to recognize autism as a central aspect of identity and culture, much like the capitalization of Deaf within the culturally Deaf community.

- Goffman, E. (with Internet Archive). (1963). Stigma; notes on the management of spoiled identity. Englewood Cliffs, N.J., Prentice-Hall. http://archive.org/details/stigmanotesonman0000goff

- Link, B. G., & Phelan, J. C. (2001). Conceptualizing Stigma. Annual Review of Sociology, 27(1), 363. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.27.1.363

- Oliver, M. (1990). The Politics of Disablement. Macmillan Education.

- Sayce, L. (1998). Stigma, discrimination and social exclusion: What’s in a word? Journal of Mental Health, 7(4), 331–343. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638239817932

- van Beukering, I. E., Smits, S. J. C., Janssens, K. M. E., Bogaers, R. I., Joosen, M. C. W., Bakker, M., van Weeghel, J., & Brouwers, E. P. M. (2022). In What Ways Does Health Related Stigma Affect Sustainable Employment and Well-Being at Work? A Systematic Review. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation, 32(3), 365–379. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-021-09998-z

- Canadian Heritage. (2020). Literature Review—Systemic barriers to the full socio-economic participation of persons with disabilities and the benefits realized when such persons are included in the workplace. https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/pch/documents/corporate/transparency/open-government/literature-review/Lit-Review-Systemic-Barriers-eng.pdf

- Hub Sociology Desk. (2025, May 6). Disability and Stigma: A Sociological Perspective. https://hubsociology.com/disability-and-stigma-a-sociological-perspective/

- Carolan, K. (2024). “It just makes you more vulnerable as an employee”: Understanding the effects of disability stigma on employment in Parkinson’s disease. Chronic Illness, 20(4), 655–668. https://doi.org/10.1177/17423953231185386

- Sebrechts, M. (2024). Towards an empirically robust theory of stigma resistance in the ‘new’ sociology of stigma: Everyday resistance in sheltered workshops. The Sociological Review, 72(5), 1117–1135. https://doi.org/10.1177/00380261231199889

- Richard, S., & Hennekam, S. (2021). Constructing a positive identity as a disabled worker through social comparison: The role of stigma and disability characteristics. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 125, 103528. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2020.103528

- Balogun-Mwangi, O., DeTore, N. R., & Russinova, Z. (2023). “We don’t get a chance to prove who we really are”: A qualitative inquiry of workplace prejudice and discrimination among Black adults with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 46(1), 4–13. https://doi.org/10.1037/prj0000527

- Rhyss, S. (n.d.). Understanding and Countering Stigma Around Disability. Canadian Disability Resources Society. Retrieved November 4, 2025, from https://www.disabilityresources.ca/blog/understanding-and-countering-stigma-around-disability

Subscribe

Sign up to receive updates from CCRW.